Walk through any upscale neighborhood, and you'll see the same thing: pristine homes that look like they've been pulled straight from design magazines, lawns maintained with military precision, and cars that gleam under every streetlight. Scroll through social media, and the pattern continues—filtered photos where every blemish has been erased, curated feeds that showcase only life's highlight reel.

Yet, for all this polished perfection, people seem more anxious than ever. The kitchen renovation that was supposed to bring joy becomes another source of stress when reality doesn't match the Pinterest board. The pressure to maintain these impossible standards leaves everyone feeling like they're falling short, no matter how much effort they put in.

But step into a traditional Japanese tea house, and you'll see something that might surprise you. The ceramic bowls are wonky on purpose, with thumbprints still visible from when someone shaped them on a wheel. The wooden floors are worn smooth in all the spots where people have walked for centuries. Out in the garden, moss grows wild between old stones, and nobody's rushing to power-wash it away. These places have a kind of calm that feels almost alien in our fix-everything, upgrade-everything world.

There's wisdom hiding in these imperfect spaces—something our endless quest for flawlessness completely misses. More people are starting to figure out that maybe, just maybe, the secret to feeling better about life isn't perfection at all. Maybe it's learning to see beauty in the scratches, the wrinkles, and all the worn-down edges that come with actually living.

How Ancient Tea Masters Got It Right

Wabi-Sabi didn't start as some Instagram aesthetic or lifestyle trend. It grew out of medieval Japanese tea houses where Zen monks and tea masters stumbled onto something profound while working with very little. The words themselves tell the story: wabi originally meant something like rustic loneliness, while sabi described how things get beautiful as they age and weather. Put them together, and you get a way of seeing that finds something gorgeous in imperfect, temporary, incomplete things.

This whole approach comes straight from Zen Buddhism, which teaches that nothing sticks around forever, nothing ever gets completely finished, and nothing is totally perfect. Instead of fighting against these basic facts of existence, Wabi-Sabi says: what if these are exactly the things that make life beautiful?

Back in the 1500s, there was this tea master named Sen no Rikyū who basically revolutionized how people thought about beauty. While everyone else was showing off with expensive Chinese porcelain and elaborate decorations, Rikyū started using rough, handmade bowls that looked like regular potters had made them in their backyards. He built tea houses with doors so low that even the emperor had to crawl in on his hands and knees—which was pretty radical for a society obsessed with hierarchy.

Rikyū's whole setup was deliberately simple: a few wildflowers stuck in a plain vase, some basic calligraphy on the wall, and those wonderfully imperfect bowls that felt good in your hands. Where the fancy crowd saw amateur work, Rikyū revealed something genuine and moving. He was basically telling Japan's elite: your idea of beauty is all wrong.

As one philosopher put it, Wabi-Sabi celebrates "things modest and humble... things unconventional." It's about asymmetry, rough textures, simplicity, and paying attention to how nature and time shape everything around us. This couldn't be more different from Western beauty standards that worship symmetry, youth, and things that last forever—think Greek statues or the airbrushed faces we see everywhere.

Why Perfection Is Making Us Miserable

Here's the thing about our current obsession with getting everything just right: it's actually making us pretty miserable. Researchers who study perfectionism have noticed it's getting worse, especially among younger people, and it's directly connected to rising rates of anxiety and depression. The problem isn't that we want to do well—it's that we've created impossible standards that leave us feeling like failures no matter what we accomplish.

The perfectionist trap works like this: you achieve something you thought would make you happy, but instead of satisfaction, you just move the goalpost further out. Nothing ever feels like enough because there's always something that could be better, cleaner, or more impressive.

This is where Wabi-Sabi offers something like relief. There's a great story about cellist Yo-Yo Ma performing when one of his strings snapped right in the middle of a piece. The audience gasped—disaster, right? But Ma said later that he felt this rush of joy when it happened. Why? Because the worst possible thing had just occurred, which meant he could stop worrying about perfection and just play music. The broken string didn't ruin the evening; it freed everyone in the room to connect with something real.

That's Wabi-Sabi in action: the flaw becomes the doorway to something better than perfection ever could have been.

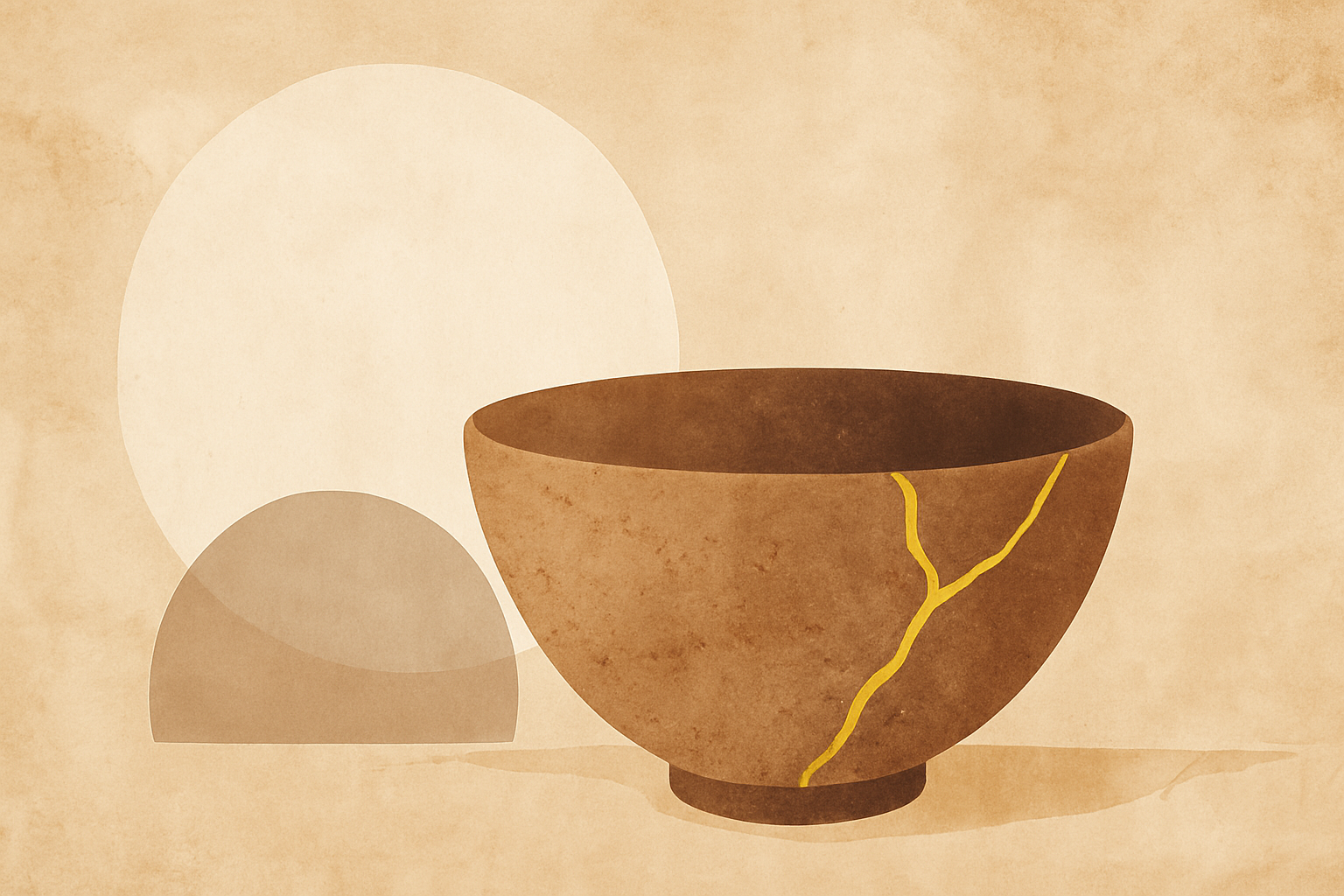

The Japanese have this practice called kintsugi, where they repair broken pottery with gold or silver. Instead of throwing out the damaged bowl or trying to make the crack invisible, they highlight it. The repaired piece ends up more beautiful and valuable than the original, with its story of breaking and healing written in precious metal across its surface.

This isn't about lowering your standards or giving up. Japanese arts require incredible skill and dedication. But there's a difference between pursuing excellence and demanding perfection. A potter might spend years mastering their craft, but when their finger accidentally leaves a mark in the clay, they might keep it there because it shows a human made this thing.

Making This Work in Real Life

So, how do you actually live this way without becoming a slacker or giving up on your goals? It starts with small changes in how you set up your space and approach your days.

Letting Your Home Tell Stories

You don't need to gut your house and start over with rustic everything. But you can start choosing things that get better with age instead of worse. Wood that develops character over time rather than laminate that just looks cheap when it gets dinged. Linen sheets that get softer with every wash instead of synthetic ones that pill and fade.

Think about that dining table with rings from years of family dinners. Those aren't damage—they're a map of every birthday, homework session, and late-night conversation that happened there. The slightly wobbly handmade mug your kid brought home from art class has more personality than anything you could buy at a fancy store.

Try decluttering, but not in that minimalist way where everything has to be perfectly sparse. Get rid of the stuff that doesn't matter so the things that do can actually shine. Keep the threadbare quilt your grandmother made, the ceramic bowl with fingerprints still visible in the glaze, that weird rock your child insisted on bringing home from vacation. When you clear away the excess, these imperfect treasures transform your space from looking like a showroom to feeling like a home.

And here's something Japanese homes do that we rarely see: they change with the seasons. Instead of permanent decorations, try putting a single branch with spring buds in a simple vase or arranging a few autumn leaves on a table. These temporary touches acknowledge that everything changes, and that's part of what makes moments special.

Daily Doses of Imperfection

Turn your everyday routines into small practices of acceptance. Instead of inhaling coffee while scrolling through emails, sit down with your favorite mug for a few minutes. Feel how warm it gets in your hands, notice the smell, and look out the window at whatever weather is happening. Even five minutes of this kind of attention can change how your whole day feels.

When things go sideways—and they will—use those moments to practice the Wabi-Sabi mindset. Spill something on your shirt right before a meeting? Take a breath and think: "Okay, this is what today looks like." You're not trying to love every inconvenience, just meeting them without the extra drama of "this shouldn't be happening."

One thing that really helps is keeping track of daily imperfections in a way that finds something good in them. Maybe you burnt dinner but ended up laughing about it with your family. Maybe you stumbled during a presentation, but it made the whole thing feel more conversational and relaxed. Writing these down trains your brain to look for the silver linings instead of just cataloging failures.

At work, give yourself permission to finish things without endless tweaking. Set time limits on projects and stick to them. The fear of not being perfect often keeps us from starting things at all. When you're okay with being imperfect, you're more likely to try new things, speak up in meetings, or put your creative work out there.

People Are Imperfect Too (Including You)

This might be the hardest part: applying Wabi-Sabi thinking to relationships. We tend to hold people to impossible standards, expecting them to always know the right thing to say or never change in ways that inconvenience us. But people aren't projects to be fixed.

That friend who's always running late? Maybe that's connected to why they're so easygoing and fun to be around. Your partner's habit of leaving coffee mugs around the house might be tied to the same creative, scattered energy that makes them interesting. You can still talk about things that bother you, but try starting from a place of acceptance rather than criticism.

The hardest person to extend this grace to is usually yourself. Instead of cataloging everything wrong with your appearance or personality, try thinking of yourself as a work in progress—not broken and needing fixing, but growing and changing like everything else in nature. Those stretch marks? They're evidence of life you created or changes your body adapted to. The tired look in your eyes? Proof that you're working hard on things that matter.

There is a crack in everything; that's how the light gets in.

— Leonard Cohen

Try being more honest about your own imperfections with people you trust. Instead of pretending you have everything figured out, admit when you're struggling or uncertain. This usually makes relationships closer and gives other people permission to be human, too.

What This Isn't About

Before this turns into another lifestyle fad, it's worth understanding what Wabi-Sabi actually is and isn't. It's not about buying distressed furniture or making your house look deliberately shabby. It's not an excuse to stop trying or to accept genuinely harmful situations. And it's not something you can just slap onto a Western lifestyle without understanding where it comes from.

Wabi-Sabi grew out of specific cultural and spiritual traditions in Japan. Using these ideas respectfully means acknowledging that background and not treating it like we invented something new. It also means understanding that the goal isn't to look like you're practicing Wabi-Sabi—it's to actually feel more at peace with imperfection.

Some people worry that accepting flaws means giving up on improvement, but that's missing the point entirely. You can still work toward goals, take care of your health, and try to do better at things that matter to you. The difference is approaching these efforts with curiosity instead of desperation and being okay with progress that doesn't look perfect.

Think of it like gardening: you tend your plants carefully, but you also let them grow into their own shapes. You don't panic when the weather brings unexpected changes or micromanage every leaf. You can pursue your goals with the same kind of gentle persistence—committed but not frantic, dedicated but not desperate.

Finding Light in Broken Places

What Wabi-Sabi really offers is permission to get off the hamster wheel of "never good enough" and notice that beauty is already everywhere around us. The worn spot on your kitchen floor where everyone gathers to talk while dinner cooks. The night you all laughed until you cried over something that went completely wrong. The scar from when you crashed your bike as a kid. The friend who shows up even though both of you are complicated people with complicated lives.

Leonard Cohen wrote something that captures this perfectly: "There is a crack in everything; that's how the light gets in." Your imperfections aren't just things you have to live with—they're often how the best parts of life find their way in. The crack in the performance that led to real connection. The break in the pottery that became a golden line of beauty. The unexpected detour that turned into the best part of the trip.

Next time you notice something imperfect—paint peeling on a windowsill, comfortable silence when no one knows what to say, the crack in your favorite mug—pause for a second. See if you can appreciate it exactly as it is without needing to fix or improve it.

Something shifts when you do this regularly. Life starts feeling less frantic and more spacious. You realize that chasing perfection was keeping you from enjoying what was already there. And you discover that embracing imperfection isn't settling for less—it's finding a way of being human that actually works.

Turns out perfection was there all along, hidden in the beautiful brokenness of real life.